The End of Globalization? The International Security Implications

Over the last few decades, globalization has created great wealth and brought millions out of poverty. Today, a combination of technology, politics, and social pressures seems to be reversing globalization. While the new technology will continue to create wealth, it will favor developed countries. The increasing regionalization of economies and differences in rates of growth will create instability and challenge international security arrangements.

The Economist defines globalization as the “global integration of the movement of goods, capital and jobs.” The combination of labor cost advantages, efficient freight systems, and trade agreements fueled globalization by providing regional cost advantages for manufacturing. Over the last six decades, it transformed agricultural societies into industrial powerhouses.

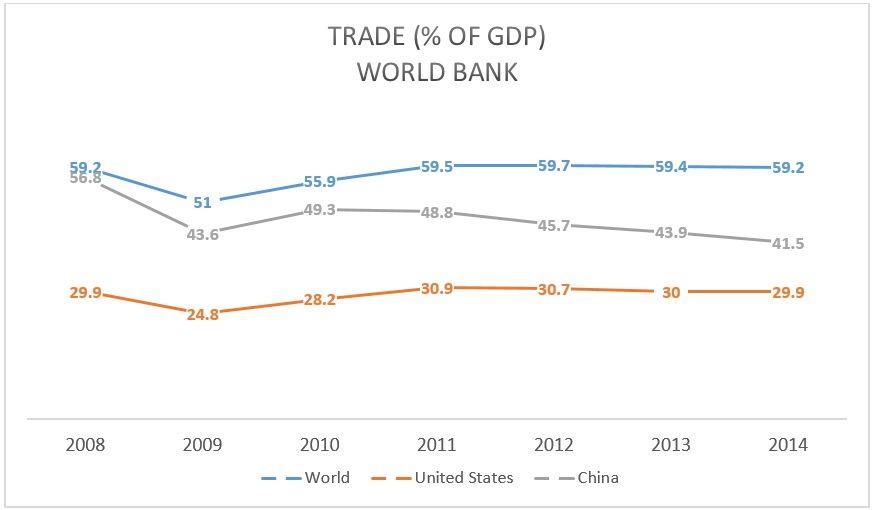

Then, the 2008 to 2009 global financial crisis slowed global trade. This led to early speculation that globalization was slowing. Yet global merchandise trade recovered relatively quickly, almost reaching pre-crisis levels by 2011. Speculation about slowing globalization ceased. Unfortunately, manufacturing trade as a percentage of GDP actually flattened and then declined from 2011 to 2014. Services and financial flows followed the same pattern.

In its 2016 report, McKinsey Global Institute reported, “After 20 years of rapid growth, traditional flows of goods, services, and finance have declined relative to GDP.” Many analysts contend that these are short term effects and trade will resume and even accelerate. I take a different view. The convergence of new technologies is dramatically changing how we make things, what we make, and where we make them. These technologies combined with trends in energy production, agriculture, politics, and internet governance will result in the localization of manufacturing, services, energy, and food production. This shift will significantly change the international security environment.

How We Make Things

The combination of robotics, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing is moving production to automated factories. According to the Boston Consulting Group, about 10 percent of all manufacturing is currently automated and this will rise to 25 percent by 2025. This is only the very front end of the shift of labor to automation. Frey and Osborne’s now famous 2014 report, “The Future of Employment” suggested that 47 percent of current jobs are at risk to being replaced by automation. The less pessimistic Gowdner report sees a 16 percent loss of jobs. Despite the range of estimates, all agree automation is coming. Between 2010 and 2013, world industrial robot installations increased by 17 percent annually; in 2014 by a further 29 percent. These figures do not include collaborative robots designed to work alongside humans. Very new, these robots represented less than 5 percent of 2015 global sales. But at an average cost of only $24,000, they will appeal strongly to the smaller companies that account for 70 percent of global manufacturing.

Even as robots are changing traditional manufacturing, 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is creating entirely new ways to manufacture a rapidly expanding range of products – from medical devices to aircraft parts to buildings. Because it used to take days to print a part, 3D printing has been used primarily for prototyping and very high value parts. Then in April 2016, Carbon3D released the first commercial version of a machine that prints 100 times faster.

Commercial firms are exploiting these advances. United Parcel Service established Direct Digital Manufacturing (DDM) focused on providing rapid 3D printing of any customer’s design. DDM’s “ fully-automated facility will house a staggering 100 3D printers which can be used to manufacture one-off parts, or mass manufacture 1,000 of the same part.” The company is also offering an in-store 3D printing service at more than 100 stores nationwide. As one journalist explained, “UPS can see a major change coming. The concept is simple, local production of a vast number of components will hit the international shipping market hard.”

Obviously, the key question is how quickly will 3D capacity and capability increase? Price Waterhouse Cooper surveyed over 100 industrial manufacturers and reported that 52 percent of the CEOs surveyed expect 3D printing to be used for high volume production in the next three to five years.

What We Will Make

To date, robotics have automated current processes but have not had a major impact on what we can make. In contrast, 3D printing will have two major impacts — mass customization and design for purpose.

The auto, truck, and aircraft parts industries see the potential of 3D printing. Rather than stocking the wide variety of parts in the spectrum of colors and finishes they use, parts makers are looking to maintain only digital files and print on demand.

More revolutionary, designers can now design an object to optimally fulfill its purpose rather than to meet manufacturing limitations. Years ago, Boeing took advantage of 3D printing’s unique capabilities to redesign a cooling duct for the F/A-18 Hornet. Instead of being made from sixteen separate parts, the part is printed as a single unit that is lighter, stronger, and optimized for air flow efficiency. Similarly, General Electric replaced jet engine fuel nozzles made from 18 smaller parts with a single, lighter, stronger, longer lasting, and cheaper 3D printed part.

3D printing can also increase the strength of a product through honeycomb construction, like that of bird bones. Very difficult to make with traditional manufacturing, 3D printing can do this with relative ease. Further, 3D printing can create gradient alloys which expand the material properties of the product. And 3D printing can actually improve the performance of existing materials. Additive manufactured ceramics can have 10 times the compressive strength of commercially available ceramics, tolerate higher temperatures, and be printed in complex lattices further increasing the strength to weight ratio.

Where We Make Things

The combination of robotics, artificial intelligence, and 3D Printing means “on-shoring,” returning manufacturing to the home market, is increasing rapidly. Boston Consulting Group noted a number of trends that support this, including an increase in the number of manufacturers bringing their facilities back to the United States, a sizeable chunk of manufacturers who would build new plants in the United States rather than China, and a majority of manufacturers who believe new manufacturing technologies will lead to localized production. The United States lost manufacturing jobs every year from 1998 to 2009 — a total of 8 million jobs. But in the last six years, it regained about 1 million of them.

Hal Sirkin, an analyst with Boston Consulting, predicts “you’re going to see more localization rather than more scale. … I can put up a plant, change the software and manufacture all sorts of things, not in the hundreds of millions but runs of five million or ten million.” The bottom line is that more and more products will be produced locally which will steadily reduce the need for international trade in manufactured goods.

Service Industries Are Coming Home Too

Service industries are following suit as artificial intelligence takes over more high order tasks. Call centers are already moving from low wage areas to server banks. Pairing AI with humans has resulted in lower costs (fewer humans) and higher customer satisfaction for United Services Automobile Association.

Nor is artificial intelligence limited to routine call center tasks. This year the Georgia Institute of Technology employed a software program named “Jill Watson” as a teaching assistant for an online course without telling the students. All of the students rated Ms. Watson as a very effective teaching assistant. None guessed she wasn’t human. Baker & Hostetler, a law firm, announced it has hired her ‘brother,’ Ross, also based on Watson, as a lawyer for its bankruptcy practice.

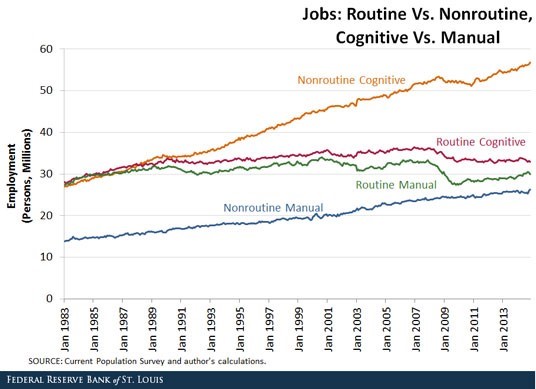

Artificial intelligence is already handling tasks formerly assigned to associate lawyers, new accountants, new reporters, new radiologists, and many other specialties. In short, non-routine tasks – whether manual or cognitive – will still be done by humans while routine tasks – even cognitive ones – will be done by machines. And this is not a new phenomenon, computer technology has been eating jobs since 1990.

With labor costs much less of an issue, better communications links, better infrastructure, more attractive business conditions, and effective intellectual properly enforcement, services are returning to developed nations. The few, more complex questions that require human operators are better handled by native language speakers intimately familiar with the culture.

Only The First Step?

The changes in manufacturing and services may be only the first step in de-globalization. The reduced demand for transportation fuels, alternative energy technologies, and increased energy efficiency are reducing the global movement of coal and oil. While starting from a small base, renewable energy — wind, solar, thermal — is growing very rapidly. In 2014, 58.5 percent of all new additions to global power systems were renewables. In 2015, 68 percent of the new capacity installed in the United States was renewable. As vehicle fuel efficiency, hybrids, and all-electric vehicles improve, the source of transportation energy will also move from petroleum to electric energy. Wood Mackenzie suggests that U.S. gasoline demand could fall from 9.3 million barrels/day to 6.5 million barrels/day by 2035. Fracking, alternative energy, and new efficiencies have already dramatically reduced the U.S. need for imported energy. If other nations can make similar advances in these areas, it will slow and then reduce the global trade in gas and oil.

Agriculture is another area that has seen increased global trade over the last few decades. High value fruits, vegetables, and flowers move from nations with favorable growing conditions to those without. However, indoor farming has begun to undercut this trade by providing locally produced, fresher, organic products. Depending on the product, such farms can produce 11 to 15 crop cycles per year. A facility in Tokyo produces 30,000 heads of lettuce per day and plans a second plant to produce 500,000 head of lettuce daily within 5 years. Now that the concept has been proven, Japanese firms are putting 211 unused factories into food production.

The industry is not restricted to Japan. A firm in the United States is planning to establish 75 indoor factory farms. Growing Underground is exploiting the concept in London. Similar urban farms are being built across Europe and Russia. These indoor farms do not require herbicides or pesticides, use 97 percent less water, waste 50 percent less food, use 40 percent less power, reduce fertilizer use, reduce shipping costs, and are not subject to weather irregularities. Scaled-up, these processes will seriously reduce the market for long-range shipping of high value agricultural products. Japanese firms are even experimenting with growing rice in a number of their facilities.

All of the factors listed above are being reinforced by social pressures to “buy local” to reduce the environmental impact of production. Local production both creates jobs near the consumer and dramatically reduces transportation energy and packaging waste. Indoor farming can almost eliminate the environmental impact of farming on land and waterways.

A further driver of global fragmentation is the effort by authoritarian governments to segment the internet. Initially considered an impossible goal, China has steadily improved its ability to control what people can access inside its territory.

What China calls the “Golden Shield” is a giant mechanism of censorship … eight of the 25 most trafficked sites globally were now blocked here. The American Chamber of Commerce in China says that 4 out of 5 of its members’ companies report a negative impact on their business from Internet censorship.

Totalitarian nations have decided the costs of connectivity exceed the benefits of globalization. Restricted access to the internet will inevitably reduce these nations’ participation in the global economy.

Cumulative Effects

The key question is how much will globalization decrease from the sum of shifts in manufacturing, automation of services, localization of power, and food production. Localizing production will dramatically reduce traffic in components and finished manufactured products thus disrupting established trade patterns. Currently we ship raw materials to one country. It puts together the sub-assemblies, packs them, and ships them to another country for assembly. There they complete the assembly and packaging, then ship the packaged product onward to the consuming country. With the emergence of additive manufacturing, we will ship smaller quantities of raw materials to a point near the consumer, produce them, and then ship them short distances for consumption. Thus reducing international trade. The localization of energy production and return of high value agriculture to developed nations will further reduce global trade.

Other factors are slowing globalization. First, protectionism is growing. Since 2008, more than 3,500 protectionist measures and administrative requirements have been instituted globally. More governments are required to purchase locally produced products, even if they are much more expensive than imported alternatives. As robotics, artificial intelligence, and 3D printing eliminate jobs, the political pressure for protectionism will rise. To prevent dumping, nations are already raising import duties.

Political campaigns in the United States and Europe reveal the growing popular opposition to international trade treaties. Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton both oppose the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Its Atlantic counterpart, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, is still being negotiated but faces growing political opposition on both sides of the Atlantic and may have been dealt a fatal blow by the Brexit vote.

While the assumption that global trade is good may still exist among American policymakers and economists, it is rapidly fading among the general population. In 2002, Pew Research found that 78 percent of Americans supported global trade. By 2008, the percentage had fallen to 53 percent. In 2014, when Pew changed the questions from whether trade was good for the nation to whether trade improved the livelihood of Americans, favorable ratings plunged. Only 17 percent of Americans thought trade leads to higher wages, only 20 percent believed it created new jobs.

Implications

Since 1945, the United States has pursued globalization for both economic and security reasons. However, for economic and domestic political reasons, whichever party wins the next election it will likely encourage each of the trends discussed in this paper with tax breaks, trade policy, and administrative actions. The cumulative effect will be to discourage and undermine the case for globalization while potentially strengthening the U.S.-Canada-Mexico trading bloc. Similar pressures may drive nations across the globe to regional trade blocks.

In turn, if globalization no longer has major economic benefits for the United States, then employing U.S. power in an effort to maintain global security will be seen purely as a cost. This will create a very different domestic environment for the practice of U.S. foreign policy. Deglobalization will reduce the American people’s interest in propping up global stability at exactly the time the widespread dissemination of smart, cheap weapons will significantly increase the costs of doing so. Faced with growing social and infrastructure needs, Americans may no longer be willing to underwrite international security with their tax dollars. Under these conditions, the United States public may demand a return to a limited strategic concept of defending the hemisphere and assuring access to the global commons. The U.S. military’s primary mission may revert to the punishment of bad behavior (gunboat diplomacy) rather than engagement to stabilize a region.

Turning isolationist would reverse over 60 years of American foreign and security policy and radically alter the international security picture. Europeans, already struggling with the implications of Brexit, will have to determine which threat – mass migration or Russian expansion – is the greater threat and how they will reach agreement on the allocation of security resources.

Asian nations will also face a very different environment. American presence in Asia has been seen as the major provider of stability and peace for the region. Given China’s recent assertiveness in the South China Sea, the biggest question for Asian nations will be how to prevent Chinese domination. In a region with no history of military security alliances, the challenges will be extensive. Some Asian states have the capability to rapidly develop nuclear weapons and may choose to do so to provide nuclear deterrence.

Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum writes:

The speed of the current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. When compared with previous industrial revolutions, the Fourth is evolving at an exponential rather than a linear pace. Moreover, it is disrupting almost every industry in every country. And the breadth and depth of these changes herald the transformation of entire systems of production, management and governance.

The 4th Industrial Revolution will unfold over the next couple of decades bringing amazing advances in manufacturing and services. There is no doubt the global economy will change in many ways. Manufacturing, services, energy, and agriculture all seem to be moving to localized production. The net effect is slowing and may be reversing globalization. If this is happening, the basic assumptions undergirding sixty years of post-World War II prosperity and security will change too. Deglobalization trends must be monitored closely and national security policy will have to be adjusted to the emerging economic and political realities.

Dr. T. X. Hammes is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the U. S. National Defense University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the views of the U.S. government. An extended version of this article is available at the National Defense University website.

Image: UPS.com